This post has been a long time coming. At this writing, it has been a little over two years and nine months since I was first diagnosed with melanoma. Treatment involved:

~ 2 general anesthetic surgeries within 2 weeks of each other. The first a procedure to remove a crescent of my ear, put the ear back together, and remove 5 sentinel lymph nodes. The second is called a neck dissection: removal of my parotid gland and 56 more lymph nodes from my face and neck. This incision stretched from the top of my ear at my hairline, down the side of my neck, and halfway across the front of my throat.

~ 3 days admitted to the hospital post-surgery #2.

~ 11 CT scans, three of those PET scans (the kind that leaves you radioactive for a couple hours), and two MRIs.

~ Well over 100 tubes of test blood (lost count around 125).

~ 5 of eight scheduled infusions of the clinical trial drug Ipilimumab.

~ An oncologist, an oncology NP, a nutritionist, an ophthalmologist, an endocrinologist, a LCSW, and LOTS of wonderful nurses.

Writing about this odyssey has been something I have largely avoided since my January 2014 diagnosis. After a few short posts in the first year, I went radio-silent on the topic.

Why?

Relatives and friends all asked if writing about it might help me. Or help someone else who has a melanoma diagnosis. To them all, I said (really, I spat it with considerable hostility) that I would not give melanoma one more second of my effort than I absolutely had to. I did not want to give this disease ANY of my words.

Ugly stuff

Melanoma is an ugly disease. It is the deadliest of skin cancers because it does not stay on the surface of the skin. No, melanoma likes to spread. To the bones, brain, lungs, and to other major organs. A metastatic melanoma tumor (Stage 4) was, just a few years ago, a death sentence.

Melanoma does not respond to conventional chemotherapy. The best way to treat it? Cut it out. Pull it up by the roots before it can spread. My melanoma was a Stage 3 tumor and had spread to two of my lymph nodes. Also historically “death sentence”-territory for many cancers, including melanoma. The statistics are bleak, something like 20% survival rate five years after a Stage 3 melanoma diagnosis.

Current post-surgery treatment for Stage 3 melanoma is also a bleak prospect. A year-long course of weekly infusions of Interferon will make the patient feel like they have the flu, for the entire time. When offered that option, I asked my oncologist, “Does it work?” He shrugged.

There was another option. My hometown teaching hospital, Wilmot Cancer Center at University of Rochester Medical Center, is host to a clinical trial that compares how well a drug (Ipilimumab) used to treat metastatic melanoma tumors in Stage 4 patients would work to prevent recurrence in Stage 3 patients. Long story short, I agreed to be a guinea pig, got into the trial, and received the test drug.

Protocol calls for an Induction Phase of four infusions each three weeks apart, followed by a Maintenance Phase of four more infusions each three months apart.

I made it through five infusions before my doctor pulled me off the drug due to side effects, of which I had three major bouts in a seven month period:

- Gastrointestinal Turmoil

- A widespread, angry rash of welts

- Hyperthyroidism

Indeed, sometimes cancer treatment is nearly as deadly as the disease. I reached the decision to stop treatment at the same moment that the doctor decided I needed to stop. “Good,” I thought—“We finally agree on something.”

Lovely Stuff

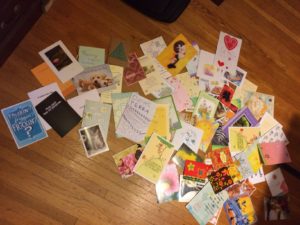

Want to find out how people really feel about you? Have a major health crisis. We had so much food delivered in the weeks after surgery, and flowers, and cards. So. Many. Cards. I kept them all, bundled in a gift bag, but had not looked at them since first opening each envelope.

In preparation for this writing, I took time to sit down and re-read every single card. All SEVENTY. At least ten of those are from my college roommate, who would frequently send silly cards with short messages. This is not even counting the letter-per-week for a year she wrote to me starting with my first infusion in April 2014. I have all of those, too.

During this re-reading, there are a handful of Get Well cards that bring me to tears. Okay, it is a shoulder-shaking, cathartic cry. All of the cards send loving, healing sentiments, but this handful of cards…wow. It’s all too personal to share, but my feelings well from deep down enough that I want to find each one of these people soon, give them a long hug, and say, “Thank you. I love you, too.”

Hating Cancer

More times than I care to count in the last 2 and half years, cancer has been the ugly diagnosis for friends and family. My mother, just a few weeks after my surgery (she is doing well now). My uncle, about a year ago. He passed away in April. Mutual friends and people at church, and their friends and family members.

One particular man from church, among the greatest individuals I’ve had the privilege to know in all my life, was diagnosed in mid-2015 and left this earth on Christmas Eve.

So many others diagnosed and in the midst of treatment right now. Every time I hear of another, it is a dagger to my heart. I can’t know exactly what they are going through, but I know what I went through. It’s an awful club to be in.

“You’re going to be okay.”

None of my doctors have ever said that phrase to me. I get it; it is probably a medical establishment-taboo to give absolute reassurance, if not a breach of hospital policy. It is a platitude. No better than: “You got this.” “You’re gonna beat this.” “God has a purpose.” “God doesn’t give you more than you can handle.”

For me, in the thick of things, platitudes were particularly infuriating. I now understand why people say them — they need to comfort themselves against the terrifying reality of a cancer diagnosis.

A few weeks ago I finally listened to Tig Notaro’s groundbreaking stand-up comedy routine from 2012, where she used the stage to talk about her own very-recent-at-the-time cancer diagnosis. It is at the beginning of her set that she first turns the idea of ‘platitudes’ on its ear. A brief excerpt, my emphasis added:

Good evening. Hello. I have cancer. How are you? Hi, how are you? Is everybody having a good time? I have cancer. How are you? Ah, it’s a good time. Diagnosed with cancer. [SIGHS]. It feels good. Just diagnosed with cancer. Oh, God. Oh, it’s fine. Here’s what happened.

It’s very personal. Found a lump.Guys, relax. Everything’s fine. I have cancer.

Somebody over here just keeps going, oh. ‘Oh, I think she might really have cancer.’ Who’s taking this really bad? Oh. It’s OK.

It’s OK. It’s going to be OK. It might not be OK. But I’m just saying, it’s OK.

You’re going to be OK. I don’t know what’s going on with me.

I could not have listened to it sooner because I could not have laughed, at all, about cancer. Only because of where I am at now can I laugh, so hard, at those last two short sentences.

“Recovery”

What is recovery? Recovery from surgery? Recovery from general anesthetic? Recovery from the shock and stress of the whole situation?

Surgically speaking, it took most of 2014 to recover. I could barely open my jaw to eat for almost a month, and when I could I had little control over my tongue and inside of my mouth, similar to a baby or a stroke patient. For example, I could not bite a sandwich without fear of biting myself, and could not eat crunchy foods for fear of choking because I could not keep track of all the pieces in my mouth. In fact, I have a purple scar on my tongue from when I treated myself to pita bread with hummus on my birthday just three weeks after surgery. I bit myself good.

The incision(s) left the side of my face and neck numb, from the corner of my mouth to my earlobe. My smile was markedly lopsided for almost four months, and still slightly droops on that side. To this day my jawline, neck, and lower earlobe are completely numb, and probably always will be. It is to this happy accident that I attribute miraculously not experiencing much pain at all at my surgery site. The doctors either didn’t believe me or expected the pain to arrive, because I left the hospital with an astonishing amount of opioids. The pills were handed to me after Surgery #1 while I was still groggy from general anesthesia so I swallowed them dutifully. I didn’t care for how they made me feel (or, rather, not feel) and therefore didn’t want them, luckily didn’t need them, didn’t take them after Surgery #2 — I turned them in to the police department’s safe disposal program.

My body and stamina suffered through the end of 2014. Physical activity was unbelievably difficult. My first outing, to Wegmans, a couple weeks after surgery felt like I was dragging bags of lead shackled to my ankles. I had to sit down on one of those benches where you usually see an elderly person resting before heading out with their cart. I thought I might pass out from exhaustion before all the groceries were bagged. No exaggeration.

For months I dealt with lower back pain. Walking and standing for any period of time left me feeling like I might crack in half at the waist if I moved wrong. Sometimes it hurt so much I felt sick to my stomach. Late in 2014, I met a massage therapist who began to work out the havoc wreaked on my back and neck from the contortions of the surgical table followed by a month of sleeping upright. Her hands are a gift and relief was nearly immediate. And, she is now an incredible friend.

The ropey scar stretching down the side of my neck from an incision closed by 17 staples is finally starting to become something that does not terrify me when I see it in the mirror. Starting to. In the first year out in public, I would sit with that side facing a wall in a restaurant; I know people were looking and staring. I saw them, their faces telegraphing, What happened to her? Sometimes now when I get a good look at that scar and my re-formed ear, I still can’t believe this whole thing happened.

There are photos of me in recovery. As of this writing, I have yet to look at those photos. Maybe I will now…. Okay. I just looked. Not as bad as I thought. Memories are flooding back about drains and blood and … let’s move on.

Overall, I don’t know if I am completely recovered, or if I ever will be. Doctors don’t typically use the word “remission” with melanoma. My surgeon (a genius and super nice guy) said that with cancer in general, the word remission is not typically used until at least five years from diagnosis without recurrence.

In other words, I am not out of the woods yet. Melanoma can, in fact, show up again 10 or 20 years after initial diagnosis.

BUT—and this is a big ‘but’—because of my treatment with the clinical trial drug, no statistics apply to me. I am in uncharted territory.

Only recently have I been able to say the words, “I had cancer.” “Had” being the operative term. I didn’t want to jinx it by celebrating too early. Up until now, I have said, “As far as I know, I do not have any cancer right now.” Or, at least as of the last bloodwork, CT scan, and checkup.

My last set was in mid-August. Around the time that something amazing began to happen.

Having Cancer

Participating in a clinical trial means a lot of follow up. A LOT. Which is good in a way, because you want them looking. But, then again, they are always looking. But not always answering questions.

Pro Tip if you are ever in a clinical trial: Answers to most questions will be “I don’t know.” You’re an experiment, duh.

Bloodwork and checkup took place every week for the first three months, then afterward with a CT scan every three months during the first two years. Every scan was preceded by a few weeks of intense anxiety, followed by a few days of euphoria after clear results. This past February I was released to six month scan intervals. But even as of my last scan in August, I am unable to concentrate on scan day or the two days that follow before I get the results. I read or watch movies, because my mind shuts down.

Thankfully, it was another clear scan. My eleventh clear scan. I have made it through two and a half years. Now, I know you want to know about this amazing thing that began to happen around this time, but bear with me. All this needs to be written.

Starting with the moment of that phone call on January 17, 2014, when the dermatologist told me I had cancer, I began to carry “having cancer” with me every single minute of every day. It was part of my conscious daily thoughts from the second I opened my eyes. “Having cancer” was always there, like air. In that first year, I died, in my mind, a thousand times.

This was especially so around the time I developed hyperthyroidism, when, along with an abnormally rapid resting heart rate, ravenous appetite, little need for sleep, and being impervious to cold, every emotion was magnified. I was inconsolable.

For most of that year, I had nothing to say to God. Not that I was angry, exactly. It was just that in those moments when a person might pray for mercy or relief, I had no words. Crickets. A good friend in whom I confided this replied along the lines of, “Don’t worry—you don’t need to pray; all of us who love you are doing it for you.”

By November 2014 (pre-hyperthyroid diagnosis) while daily walking three miles through snowy woods during my period of sweaty mania, I started to make deals with God. A “Take this from me”-prayer was born on those walks. Can prayer cure cancer? I…just…don’t…know. Those were the words that made the most sense to me.

Last winter, almost a year later, I realized that this prayer was answered. Gradually, I had gone from going hours to days to weeks without thinking about cancer. I could work, have fun, get back to growing my freelance business, and make plans.

I could forget about it. Prayer answered? I did ask God to “Take this from me.”

But, preparing for scans-bloodwork-checkup never failed to remind me: I might still have cancer.

Speaking of forgetting

Memory is mysterious. Wonderful. Frightening. I have always had a talent/curse for vivid memories. I won’t say I have a photographic memory, but it is pretty close, and is something I admit to valuing about myself—it has helped me to learn, to succeed, and to look back over my life like a movie.

After a cancer diagnosis and two general anesthetic surgeries, I am even more in awe of memory. Because I lost so much of mine.

It begins with being wheeled into the operating room, feeling the intravenous anesthetic beginning to work. I am, as the anesthesiologist quips, a cheap date. I go down fast. I see the bright lights overhead, and also a workplace-safety poster about how to move a patient. At least I think that’s what it is. I look up at it and ask the nurse, “You don’t really need that, do you?” She laughs.

The next thing I remember is waking up in recovery. That in-between time, those 4-5 hours of surgery? NOTHING. It is like I did not exist during that time. Terrifying.

And from that point outward, my memory is distorted, like how light, time, and space is bent around a black hole. The distortions in my memory stretch back to three or four months before my January 2014 diagnosis through the summer of 2015. There are snippets of clear memories here and there, like pin-pricks of light:

- Seeing myself in the bathroom mirror of my hospital room and exclaiming, “I look like Frankenstein!”

(Everyone said, “No, you don’t!” …Liars.) - Vomiting all over myself in my hospital bed, and the nurse sending everyone out, cleaning me up, and hugging me as I sobbed.

- My sister-in-law, also a nurse/saint, unhooking my IV and walking me to the bathroom several times overnight my first night in-patient. In between working long shifts, working her clinical requirement, and taking master’s classes.

- A pastor friend visiting me and saying it looked like I had a run-in with Sweeney Todd. (He wasn’t wrong.)

- Watching Shirley Temple as “The Little Princess” on TCM, while cranky and impatiently waiting to be discharged.

Me and Elsa enjoying a blanket made with love. - Getting home and weeping in the shower because of everything, with The Husband half-in the shower holding me up because I couldn’t balance on my own.

- Watching the Hallmark channel all day for days (weeks?) after my release (Frasier, Golden Girls, Little House on the Prairie).

- A best friend combing dry shampoo through my hair.

- Another best friend coming to visit from NYC four months later. I don’t remember much what we did, but I remember her being here.

- Another best friend crying with me and hugging me in my doorway when I wanted to end treatment because of the real possibility of side effects killing me.

- Sleeping under the blanket made by that same friend and her family. It was waiting for me when I got home from the hospital.

- And yet another best friend writing to me a beautiful reassurance that there is a place inside me that is pure and untouched by cancer.

- Visiting the Adirondacks eight months after surgery, and feeling disappointed at discovering that those mountain trails were now too hard for me.

Besides my parotid gland, 61 lymph nodes, and part of my ear, my memory during that time is something else I will never get back from cancer. Maybe it’s for the best.

Finally, the amazing thing

In the weeks before I found out I had side effect-induced hyperthyroidism (late autumn 2014), I started to see a counselor. The fear and anxiety were oppressive. For the first few visits, I sat on her couch and sobbed. Later, after my hyperthyroidism diagnosis, she would remark, “Well, that explains a lot.”

There are two big takeaways from my time with her:

- As for my dying in my mind every day? “Don’t misuse your imagination.” Whoa. Life-changing advice.

- Me: “I can’t write.” For clients, yes. For me, nope. She said to be patient with myself and my healing, that creativity would come back.

This summer, right around my last scan-bloodwork-checkup, it did. A dam-burst happened. So. Much. Writing. So. Many. Words. What am I writing? This post, for one thing. Plus a stack of ideas for more posts. And, something else, just for me.

What changed?

When I had that eleventh clear scan-bloodwork-checkup, something clicked. A realization of the obvious that was not-so-obvious to me all this time.

I didn’t die. I am not, currently, dying. It is as if I can finally believe I’m making it. I am alive.

The reverberations have been fantastic. I want to sing, dance, and laugh. All the time. I feel like the ‘me’ that I am now is not simply a post-cancer me, but someone new. Me, in bold.

I don’t know what will happen next. I don’t know if my next PET-bloodwork-checkup in February will be clear or not.

I do know this: The Husband and I went back to the Adirondacks last month. It was two years since our last visit—the visit just eight months out from surgery when I felt like I no longer had the stamina for hiking mountain trails. In fact, ahead of this 2016 visit we both were dreading finding out just how out-of-shape we had become two years hence.

We plan to hike two of our favorite easy trails, and pick a new trail: Pitchoff Mountain. Based on the description, it ranks among the moderately harder trails we’ve hiked over the years. We take it slow, agreeing that there would be no shame in turning back if we decide that was best for our safety. We check-in throughout the hike, always deciding to press on.

The last half mile features 100 foot ascents for each tenth of a mile. It is hard. We push and pull and quietly encourage each other over boulders the size of small cars. Both of us silently dreading traversing that section on the way back down.

The summit of Pitchoff is mostly bald, meaning exposed rock with yellow paint blazes pointing the safest pathway. When I finally make it, touching my boot to the first blaze and striding out onto that summit, I feel a surge. Energy? Happiness? Triumph?

I ball up my fists and shout to the wind and the surrounding peaks, “THAT’S RIGHT, MOTHERF*CKER!!!”

(Sorry, forgot to mention that profanity came back after cancer. You go through all this sh!t and try not to yell F*CK at particularly weighty moments.)

The summit of Pitchoff does not disappoint. It has the best 360⁰ view of the Adirondacks that I have ever seen. We spend over an hour soaking it in, and I bond with Pitchoff Mountain that day.

The descent of any mountain trail is always harder than the ascent, and Pitchoff is no different. I reserve my final judgement until we are safely off the trail and in the car, but this is in my mind the whole grueling way down that mountain:

I am stronger than I thought.

My sister-in-law, the saintly nurse practitioner, often repeats this bit of truth:

None of us are getting out of this alive.

Since conquering that mountain trail and the next day watching the Ausable River bubble over rocks outside our rented house, one thought has dominated my entire being.

Right now, I feel so fucking alive.

The view from Pitchoff, filmed by me just after reaching the summit:

Adventures in Babysitting: Boys of Summer

Adventures in Babysitting: Boys of Summer

Amazing …….Thanks for sharing!!!! I have not seen or talked to you in 25 years but you have not changed a bit!!!!! Rock on with your bad self.

Wow, Terra . . . tears in my eyes. So happy that you came out the other side in one piece. Waiting to read your fiction . . .

Thank you, me too! …Some future fiction…the current one is just for me. 😉

Terra you are a beautiful soul and an Inspiration. You have spunk and strength that I love. I’m so grateful you shared your story. Thank you!

Thank you, Sheila. 🙂

I enjoyed reading your story and getting to know how you feel. It never seems to be the appropriate time to unload and express feelings of worry or frustration. But it seems that this should be what we express instead of the brave face when we are going through trauma in our lives. Thanks for sharing such intimate feelings.

Terra, you are one of the strongest people I know. Thank you for taking the time to write this. You are truly amazing❤️❤️

Thank you for taking the time to read, Gina. People always see this as “being strong” when, in fact, in the middle of it all I was anything but. It’s just doing what you have to do. Maybe that is strength, but it doesn’t feel like it at the time.

Terra your writing has always had an impact on me and this piece more so than any other.

Having worked in acute medicine for nearly 20 years it has become easy for me to be stoic about my patients and their individual struggles. It is always patients like you that remind me what we’re fighting for and why we fight so hard. It often feels like such a solo fight for the patient but there are always, as you found, inumerable amounts of people fighting right beside and even behind you.

You are fucking alive! And that breathes life into me as well!

Wow, thank you, Maryann. 🙂 I’m here because of all the people fighting beside and behind me. Sometimes I think this was harder on them than on me. And nurses? RESPECT. I will never forget Linda, the nurse who cleaned me up that first night. Keep doing what you’re doing. It’s good to be fucking alive!!!

Yes! The nurses I’ve had the privilege of working with through the years are rock stars! Nothing but respect for that profession. They put humanity back in a sterile environment.

Maryann, I vaguely recall maybe you were in the nursing program at EC…what exactly are you doing now “in acute medicine”?

Nope. I was never a nurse (that was Todd’s major ????).

I’m a Medical Speech-Language Pathologist. So, I work in the hospital setting with strokes, TBI, laryngectomies, head/neck cancer, dementia, etc etc etc.

The majority of what I do is diagnosing and rehabing swallowing dysfunction, similar to what you describe in your post.

Oh, ha, Todd-E, that’s right! …My ‘swallowing dysfunction’ was probably mild and unexpected. I ate mostly soft foods in the hospital. When I was released and got home, there was a giant tin of popcorn on the counter that someone had sent. I opened it and stuffed a few pieces in my mouth…then almost choked to death!

Terra, thank you for sharing your story. I was not aware you went through all of that.This is a very powerful, real and moving piece. I am happy to see that cancer certainly has not taken your sense of humor or your amazing way with words. My wish for you is continued clear scans so you can keep climbing those ADK trails and continue blessing us with your writing. Cancer has touched way too many people that I care about and my next door neighbor has a saying I love…”Fuck Cancer!”

Thank you for reading, Robin, and for your kind words. This piece is my very own FUCK CANCER. 😉

I knew you were pretty amazing all those years ago when I first got to know you, but I realize now that I had no idea. You are so fucking alive, as is this piece, and for all of that, I am beyond-words grateful.

Dawn, I am in awe of you every day, and so grateful for you, too. Thank you for seeing all that I poured into this piece.

Oh, Terra, I was never aware of the extent of your cancer struggle. Not having personal experience with cancer (so far, anyway), even with family or close friends, I guess I just tried not to think about it. Now I want to give you a big, long hug and encourage you to go far with your amazing creativity. The world needs you. I do, too.

Diana, it’s okay that you didn’t know. But I will take that hug next time I see you. I need to give you one, anyway.

You know I dont always want to be the one talking business when you are talking deep stuff (but I am). This writing seems perfect for a magazine.. maybe not all of it but a short version.. maybe Real Simple or – I’m a big fan of UK magazine “Red” which features many transformational stories such a yours…

Hmmmm. Thanks, I’ll give it some thought!

Terra..sobbing as I read this. You are an amazing, strong woman. No one should have to go through what you went through, but you did it with the quiet grace (minus a few swear words!) that is you. I am so happy that you are able to laugh and enjoy life again. You deserve nothing but the best. Shout out too to my extraordinary children..the Husband who was capable of things I did not know he would be able to do and the saintly nurse practitioner who underestimates the love and compassion she gives to us all. Love you.xoxo

Thank you, Mare. All of us have shed a lot of tears on this odyssey. As you know…I’m ready for more laughter! And, yes, I am grateful for your extraordinary children!!

Beautiful. Terra! You, your words, and your evergreen spirit!

Thank you, Robin. 🙂

Thank you for writing this!

Thank you for reading!