Not long ago I came across an old driver’s license issued to me in 2000, when I was 27 years old. Driver license photos do not tend to be the most flattering likeness of a person, but as I peer at a  seventeen-years-younger me through the reader-portion of my progressive lenses, I think to myself, “Huh. Pretty cute.”

seventeen-years-younger me through the reader-portion of my progressive lenses, I think to myself, “Huh. Pretty cute.”

Shortly after while leafing through photo albums from college, I pause at one photo, from my freshman year, thinking, “Awww, she’s adorable!” And at another, from a formal event at the end of my junior year, “OMG. She is beautiful...”

What did I think of myself at ages 19, 21, and 27?

“Meh.”

And what do I think of myself now, at age 44? A little better than “Meh,” but only just “Not bad for a broad my age.” I suppose I will need another buffer of 15-20 years to look back and see myself in a better light.

Women contract this self-image affliction early and we carry it all our lives. Our perceptions and definitions of physical beauty are too often shaded by our sense, either underlying or very much conscious, that we ourselves do not fit those definitions, that we are not good enough.

Self-image tends to be a complicated topic for women.

Why?

An Ugly Duckling

The Hans Christian Andersen story of The Ugly Duckling spoke to me as a child. In it, an awkward, ‘this one is not quite like the others’-duckling* is ostracized by its peers. Eventually, it grows into a beautiful swan and finds happiness and acceptance.

*Turns out a swan egg got mixed in with the duck eggs, so the hero of the story was never meant to be like the others anyway.

While I identified completely with the ugly duckling, becoming a swan seemed at best far-off, and at worst, unlikely. It is not that I craved to be beautiful and ‘like all the others’. Rather, I just wanted to blend in; while I was probably never meant to belong doesn’t mean my younger self understood that. I craved acceptance. Don’t we all?

This next part is my confessional reality:

As a child, I was the dark-haired, dark-eyed, quiet, runty, brooding, tomboyish younger of two daughters. My sister was (still is), blonde, green-eyed, fair, dimpled, socially outgoing, and perfectly at home in dresses, jewelry, makeup, and party shoes (and later high heels). The difference between us was seemingly set at birth: My name is the Latin for ‘earth’. My sister’s name is associated with diamonds, sterling, and fine objects.

[Sigh]On top of that, my mother has always had a flair for dressing stylishly, perfectly coiffed, and impeccably made up.

[Sigh]

Me? My favorite childhood sneakers were bright green Incredible Hulk-themed, and I wore a New York Yankees ball cap pulled low over my eyes for as long as I could get away with it. There are special-occasion photos of me crammed into a dress and tights… looking very much like I would bite anyone who got too close.

My mother would lament, “Awww, Terra, but you look so pretty!”

That word: Pretty.

At 5 years old, it incited a nameless, volcanic rage.

I could not then and to this day still cannot fully articulate why. All I can figure is that the dress felt ridiculously uncomfortable and impractical, and calling me “pretty” somehow meant “not strong.” The word felt as wrong on me as the dress.

Pretty meant not playing rough outside and not doing adventurous things.

Pretty meant being still and quiet.

Pretty meant being looked at and evaluated.

It meant something about what people decide they see on the outside only, not about who I am.

Being called “pretty” felt…humiliating and demeaning. Disempowering.

“Pretty” was something I decidedly was not…and I was okay with that if it meant I could play and get dirty. If everyone else could let me get on with all that I wanted to do and be, that would have been great. The pressure was to not only wear the frilly dress, but to like wearing it and to like the attention. That didn’t work for me.

In the 1970s and early 80s for girls, it was all about being “pretty.” I suspect in many ways it still is.

Awkward Teen Problems

Blending in is the goal of most teens. Even me. As my sister blossomed into a teen and fulfilled all of my mother’s wishes for what a daughter should look like and how she should embody the feminine archetype, I lagged behind. Mom was in charge of buying my clothes, and the pressure to fit in being intense and not wanting to disappoint mom, I wore the cute shoes, tops, and printed jeans that were given to me. We didn’t want for things, but were nowhere near spoiled; my mom just wanted me to be happy and fit in, and I rarely had to wear hand-me-downs.

As much as I was desperate to protect my individuality, every day I couldn’t help but compare myself to my cute, brighter-than-life, stylish sister. That’s one of the bitter ironies of being a teen: I want to be myself, as long as I blend in.

Then, when I was about 14 years old, my sister’s boyfriend turned to me as we all waited for a table at Friendly’s and declared, “Terra, you have a really big nose.”

Now, to be fair, I did inherit the genes of my maternal Sicilian grandparents. Yes, I got The Nose. As a young teen, I had not grown into it.

His comment didn’t merely sting the confidence of a young, awkward teen girl.

It utterly destroyed me.

That he would:

A) Notice the size of my nose, and,

B) So callously and bluntly announce his observation in public—there has never been a worse moment of self-image-hating in my life.

I was the Ugly Duckling, with no swan in my future. I was evaluated, found “less than,” and humiliated.

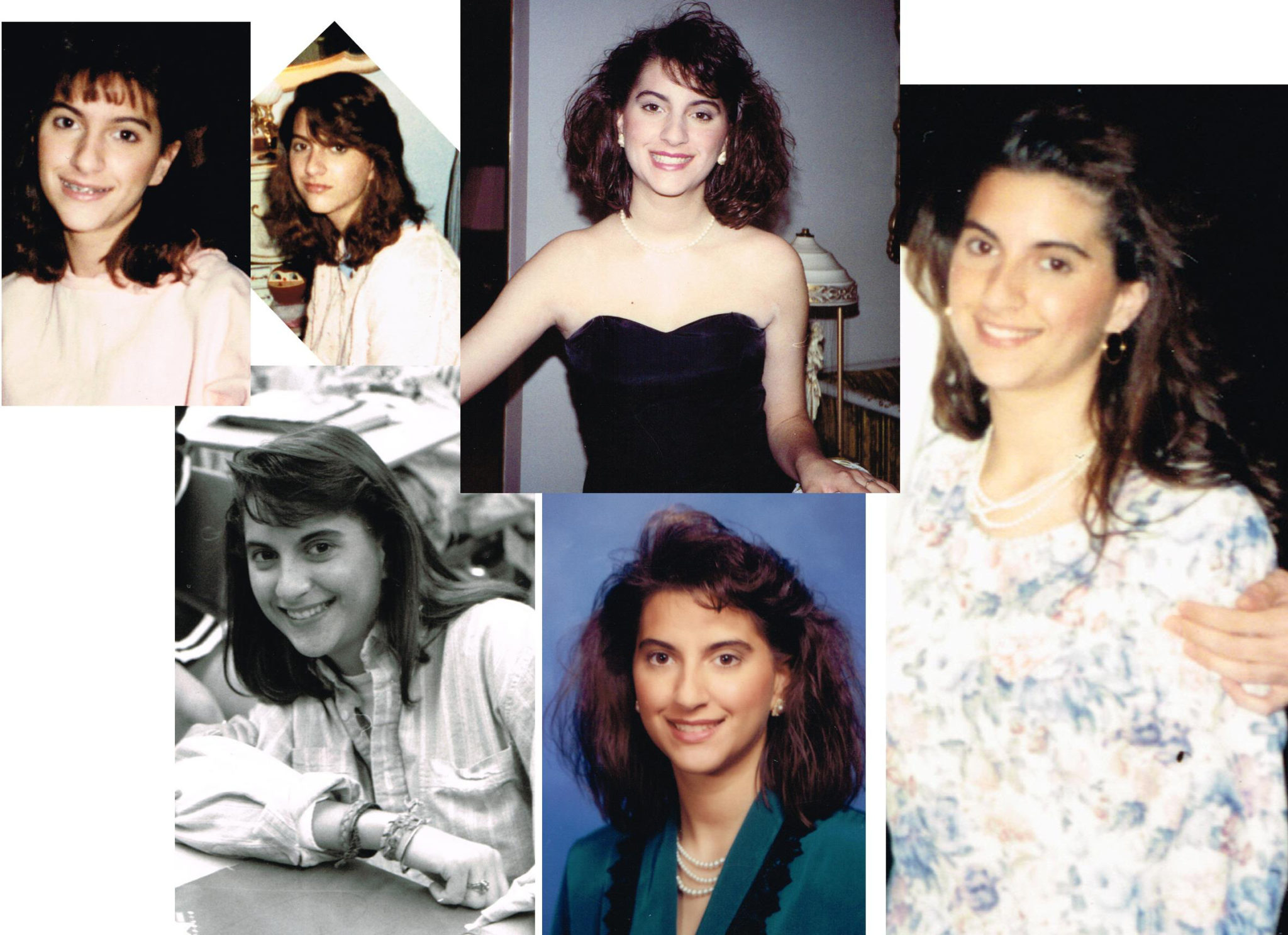

My self-image was horrible. So, I tried looking like all the other girls—I wore costume jewelry, cute shoes, purple eyeshadow, and nail polish. I got my hair permed. I wore braces to correct an overbite. I dutifully did what was asked of me by society to outgrow that Ugly Duckling phase, but always felt anxious and lacking in the trying.

Gradually and unconsciously, I stopped trying so hard.

By my senior year of high school, I had grown out my perm and wore my hair as it wanted to be–straight and simple. (For special occasions, I still bowed to the obligatory 80s big hair. I know how to use a curling iron and hairspray!) I stopped wearing eye shadow and lipstick. My footwear was either K-Swiss Classics sneakers, or brown docksiders. My jeans were worn, baggy, and bleached, and my flannel shirts were button down, all pre-dating grunge by at least 5 years and pioneering my own “shabby-preppy”-style rooted in comfort.

I began to evolve into Me, if not into a swan.

The Deal With Hair

Do blondes really have more fun?

Should a woman always color to conceal gray?

Why do grandmothers cut their hair short?

Women are obsessed with hair. A woman’s hair is often the cornerstone of her femininity, a true crown to her total self-image. Color, length, and style telegraph volumes: how much time and money she spends, how she wants to be seen (or not seen), her age….

Spending the majority of my young adulthood with usually long, usually straight hair meant constant grooming. The texture of my hair is fine, so it would take an oppressive amount of time, energy, and hairspray to achieve anything close to mid-1980s big-hair. Then I would have to protect it from rain, wind, and the general motion of living life.

Eventually opting to leave it straight freed up some breathing space, but it wasn’t until I cut all my hair off in college for the first time that I felt immediately empowered. Since then I have rocked many a pixie or short shag style, and haven’t combed my hair in years. (This is a story in itself…more on this later….)

All that’s left is waiting for the gray to grow in.

Shades of Gray

Why can a man let his hair gray naturally, on its own timetable, but not a woman?

Over the past couple of years, my friend Josephine had mentioned many times that she wanted to stop coloring her hair to cover gray. She is naturally dark-haired, so letting her gray grow in could be an awkward transition since she had been coloring to cover encroaching gray for years. Many people discouraged her, saying over and over that it would make her look “old.”

Time would go by, Josephine would mention it again, and I would always tell her to go for it. What did she have to lose? If she hated it, just color it. Finally, last summer, she found a way to try it: her stylist added gray highlights throughout her hair so that her natural gray could grow in without the awkward transition.

She. Looks. Stunning. It is an inspiration to see her — a vibrant woman embracing her natural self. Not that some people have not occasionally chastised her for not coloring to look younger (shame on them!), but at least now she feels empowered enough to push back and own her gray. Every last streak of wisdom.

Gray Areas

On the other hand, I can concede that whether or not to color her hair is completely up to the individual woman and what makes her feel good about herself.

My Mom has always had jet black hair, and had been coloring it as long as I can remember. In fact, I once asked her when she started to really go gray, and she had no idea because she had been coloring for so long.

When her hair began to grow back after chemotherapy, she continued to wear her wig until she had a shag of about 4 or 5 inches long. It was a shiny silver mane, with remnants of dark peeking through at the back. Even my sister, who has been highlighting and coloring for her entire adult life, agreed it was gorgeous.

But Mom just didn’t feel like herself. In the end, I couldn’t blame her for coloring that beautiful silver mane; when well-meaning people suggested I could grow out my hair to cover the scars of surgery on my ear and neck, I was appalled. That wouldn’t be me.

The Costs of Beauty

I get it, Mom. You are not alone. According to this 2015 article from The Atlantic, an estimated 70 percent of women in the U.S. use hair-coloring products. That means nearly 3 in 4 women got the message that what they look like naturally is not okay. The cosmetics manufacturing industry overall made $255 billion in revenue globally in 2014. Global profits are estimated to increase to $316 billion by 2019.

I’m not immune. I keep on-hand a box of teeth-whitening strips and use one or two every few months. My Mom taught me at an early age to use moisturizer and eye cream—even as I have tossed aside most other cosmetics, skin care is something I admit to continue to invest time, money, and attention.

It’s not about wrinkles; I have those I and don’t much mind them. It is the damn acne! How is it that I have wrinkles and acne?! It is the gift of roiling female hormones—with the empowerment of owning my 40s has come another round with acne. [Sigh.]

When I dare to wonder why women color their hair, I just have to remember how completely deflating it can be to face the day with a new acne breakout.

Back in the 90s, one close friend from college took the infamous acne drug Accutane to treat cystic acne. It was nasty stuff. Not only did it wreak havoc on the rest of her skin, making it sometimes painfully dry, she had to submit to frequent urine tests (presumably to check for toxicity).

As Accutane fights acne, skin can scab, including on the face. A horrible irony.

Did Accutane work? It did. Cystic acne was stopped in its tracks, putting an end to painful and disfiguring outbreaks. Her complexion cleared and remains clear, and she says she would not only do it again, she would let her daughters do it if necessary.

I guess that is always the subjective question when it comes to matters of beauty and self-image, and what you can do to feel better about yourself.

Is it worth it?

When “Pretty” Becomes Sexual Objectification

For women, on one end of the self-image spectrum is health and wellness. On the other end is sexual objectification.

We want to look and feel healthy—our skin, our hair, our nails, our shape. But at some point, how we feel about ourselves and how we view these parts of our bodies are outweighed by how others see us. The opinion that should matter the most—our own—in practice winds up mattering the least. The truth is, those external opinions are meant to contain us as sexual objects rather than human beings.

Do we become complicit in our own objectification?

This study defines Sexual Objectification Theory:

Sexual Objectification (SO) occurs when a woman’s body or body parts are singled out and separated from her as a person and she is viewed primarily as a physical object of male sexual desire. Objectification theory posits that SO of females is likely to contribute to mental health problems that disproportionately affect women (i.e., eating disorders, depression, and sexual dysfunction) via two main paths. The first path is direct and overt and involves SO experiences. The second path is indirect and subtle and involves women’s internalization of SO experiences or self-objectification.

… women to varying degrees internalize this outsider view and begin to self-objectify by treating themselves as an object to be looked at and evaluated on the basis of appearance. Self-objectification manifests in a greater emphasis placed on one’s appearance attributes (rather than competence-based attributes) and in how frequently a woman watches her appearance and experiences her body according to how it looks.

Sound about right, ladies?

To be clear, Sexual Objectification happens to every woman, beginning as toddlers being praised for how pretty they look in a princess costume* and continuing on to “a certain age” when women are simply ignored, if not savagely critiqued.

When do we get to be fully comfortable in our own skin? That toddler girl knows she feels something amazing when she puts on that princess costume, and she wants that intoxicating attention the rest of her life.* Seems harmless. Is it?

* If she is cisgender! If this child declared female at birth self-identifies as male, the dress and the fawning attention to femininity may feel like the flames of hell, making this attention to appearance even more excruciating.

This evaluation of appearance is taught early to both girls and boys. It is also perpetuated by both women and men. Yes, women, we are complicit. I could argue that we are long-programmed and trapped in this cycle. What do we say when we run into a girlfriend?

“You look great.”

We mean it as a compliment, but what we are really saying is “I have just now evaluated your appearance.” Unconsciously. And it is true.

Vanity vs. Valuing

The documentary Embrace thoughtfully examines the topics of dieting, cosmetic surgery, the magazine modeling industry, and idealized body type versus the true, beautiful bodies of women. When an editor of Cosmopolitan magazine admits that clothing brands don’t want to see their products showcased above a size 8, it becomes clear that published images have brainwashed us all, men and women alike.

Fashion photography, including what happens to those images in Photoshop, creates a standard image of woman few of us have any chance of obtaining or sustaining. Remember that Dove commercial? Even the photographed model doesn’t look like herself in real life.

The fashion industry has defined body type ideals throughout history. Even our own recent past saw a duel play out in magazine ads between the curves of Cindy Crawford and the ultra-lean physique of Kate Moss.

Those body ideals spill out of the magazine and into everyday life for women. We are shamed if our breasts are too small, and shamed if they are too large. If not shamed, we are often certainly noticed first for our chests before anything else. When women choose surgery to augment or reduce their breasts, it’s hard for me to judge their reasons.

A woman’s self-image defines every aspect of how she moves through life, in ways both wonderful and awful.

Challenging Gender Norms

Wrapped up in Sexual Objectification and Self-Image is gender. And I note this realizing that I have been writing this piece from the comfort of my cisgender female perspective. Western society is frustratingly binary on gender. You are either male or female — and you had better look the part.

A reductive view for argument’s sake:

If your body parts at birth fit the accepted profile of “male,” then you must be physically strong, emotionally reserved, and assertive if not aggressive in interpersonal exchanges.

If your body parts at birth fit the accepted profile of “female,” then you must be delicate, you are allowed to be emotionally expressive, and you must be submissive in interpersonal exchanges (especially with males). Additionally, you should ideally have, and work hard to accentuate, the assets that are appealing to heterosexual males.

In other words, if you don’t fit neatly into the “girl” box, get ready for a rough ride through life.

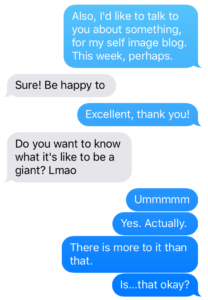

A female friend of mine is 6’3”, a height she reached in the 10th grade. She went on to play Division I basketball in college, where that type of height among women is the norm. When I first texted her about talking about this blog, she asked me:

“Do you want to know what it’s like to be a giant?”

In that moment, I felt terrible, replying sheepishly, “Yes. Actually.”

Not only is she well-above-average tall, she also has a very short haircut. The combination of size and short hair results in a phenomenon that cisgender straight women are largely ignorant of—being “Sir’d.” I.e.: People out in public sometimes mis-gender her, calling her “sir”—sales clerks, people she might hold open a door for, etc.

This is at least an example of how people moving through the world do not take the time to fully see their fellow human beings. She says some days “being Sir’d” makes her angry. Some days she is amused. It depends on the day.

Sometimes she is fearful.

Especially when the “sir” happens in the women’s restroom:

“Sir! Aren’t you in the wrong place?”

No, in fact, she is not in the wrong place.* But because the person asking has taken a hostile stance, this now becomes a safety issue. So much that she will avoid public restrooms altogether. Simply because she does not fit the archetypal western feminine image of what a woman should look like.

*(In case there is any confusion about bathroom use: Any human being visiting any restroom because they need to relieve themselves is not in the wrong place. Period.)

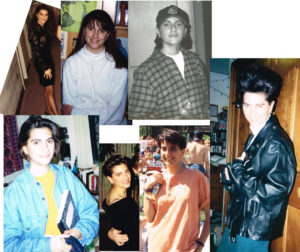

She is unapologetic about presenting as what society may classify as, she says, “androgynous,” fully embracing the freedom to explore both masculine and feminine fashions. Today, maybe a dress. Tomorrow, a shirt and tie. Admittedly, men are not afforded the same latitude in attire.

Fitting in is so overrated.

When the Ugly Duckling Swims Away

Away at college, without my sister to feel inferior around, and without my mother tsk-ing over whatever non-pretty outfit I chose, I further rejected the images of archetypal femininity, even if I didn’t know that’s what I was doing. Wanting to fit in/be perceived as attractive and desirable was replaced by wanting to feel respected and powerful.

I pushed the envelope further. Halfway through college, I cut my long, straight hair 4 times over as many months, until finally going all the way to a super short style.

It. Felt. Great.

I instantly felt like this was Me. More than twenty years later, and I think my mother still has not completely gotten over it. (And I’ll never grow it out.)

By the time I graduated college, I had two tattoos and ten ear piercings. I still wore a dash of eyeliner and my wardrobe was classic-preppy for the workday.

Today, all but two of the ear piercings are gone, but I am up to seven tattoos. I rarely wear makeup, and when I do, it is just a little to even things out. And, I recently acquiesced and tried hair color myself — purple!

What began as a rebellion against archetypal appearance spread into how I would move through and engage with the world. In most settings, I don’t blend in. And I don’t care anymore.

Most days, I am still in jeans, t-shirt with flannel, and Doc Martens boots (the same pair, 20 years on). I certainly don’t conform to or present as archetypal feminine.

I am comfortable with my image. I own my Self. I feel powerful.

And, sometimes, I feel like a swan.

Note: This topic is enormous. I’ve scratched the surface only, and admittedly wrote from a very subjective position. I don’t have it all figured out, and suspect there exist better, in-depth pieces that peel away the layers in a more organized, academic manner. My blog posts, as always, are my opinion and my musings, and are certainly not meant to be an exhaustive analysis or authority on any topic. Except for me — I own being the authority on ME!

Lastly, I’m not fishing for beauty compliments. 😉

Rocks Calling: Confessions of A Petraphile

Rocks Calling: Confessions of A Petraphile

This is an interesting look at what we all SHOULD know, which is that we should accept ourselves as we are. I have not done hair color, but I did have acrylic nails for at least 15 years, I don’t leave the house without some basic make-up, and I haven’t been happy with my weight since I was in my teens. I have great admiration for people who wear (and sometimes even flaunt) their natural features proudly.

It is a complicated landscape for all of us, for sure.

Oh, Terra, this is so epic. There’s so much I relate to in your words, and I think so much about my own self-image as I watch my 11-year-old daughter go through ups and downs in her own self-esteem about her appearance. Thank you for sharing your perspective!!

Dawn, I strongly encourage you (and anyone reading!) to watch the documentary Embrace. I believe it is on either Netflix or Amazon Prime. I think it is probably appropriate for Red to watch, too. As always, your opinion matters to me. Very much. 🙂

I relate to so much of this, especially feeling “meh” about my looks when I was younger. I refuse to color my gray even with both my sisters asking me why I don’t. I. Don’t. Care. About. It. Period.

Grace, keep slaying it and owning your gray!

This is a beautiful examination of the big picture of how we present ourselves and see each other. Thank you for creating it; in this historical moment of lurid accusations, we need to think about what the best choices look and feel like.

Great job Terra! Cant help but feel you have the start of a whole book here- or maybe the start of a series that could go in any number of directions!